Eat a carrot

The way we're making thinking efficient is surprisingly similar to what we did to food

If you and I hang out a couple of times, you’ll quickly find out that I am intense about food quality. My friends would joke whether a restaurant clears my “no industrial slop” bar, or let their eyes glaze over when I over-explain the origins of dinner ingredients. When my husband and I recently started shopping at Costco, I spent a week researching what’s sourced from where to know which of our expensive Whole Foods staples I could replace (tomato sauce - yes; pesto - no).

My explanation is that my parents have always been foodies, but not in the fine-dining-for-dinner sense. I grew up in a small Polish town in the late 90s and early 2000s, so that scene was limited; they both worked local government jobs, so there wasn’t a lot of budget for going out either. We ate at home. The reason I call them foodies is this: their bread always came from the same baker, because they knew the ingredients. Always went to the same butcher, who had cuts of meat set aside for them, and if he needed to occasionally sub out with another supplier, he’d give them a heads up (and they’d usually skip the purchase). They have an egg lady and a raspberry guy. You could drop them in the middle of an unfamiliar farmers’ market anywhere in the world and they would pick the best produce going off of scent and the test-squeeze alone.

***

It’s hard to be this type of foodie in the US, because this culture has a tendency to industrialize and efficiencize. Michael Pollan’s In Defense of Food gives a good whistle-stop tour of industrialized food, starting from the food chemists of the 1840s, who first had the idea that we don’t need food, exactly, as long as we can extract and optimize the key compounds. In the 1970s, under the lobbying pressure from the food industrial complex, policy shifted from treating food as, you know, food - a carrot or a piece of broccoli or a glass of milk or a chunk of beef - and focused on its elements. Nutritionism was born.

It assumes that regardless of the form, as long as we provide the same compounds, or nutrients, we’ll get equally healthy results. That’s a fine assumption but it fails in practice, because it turns out it’s really hard to deconstruct what the full list of necessary nutrients actually is. We assume that what we (technology, science) know at any given time is all there is to know. First, food science missed vitamins, then it missed stuff like antioxidants and flavonoids and others that are critical to the gut. Over time, it has obviously learned and improved, but in the meantime it left a trail of poorly nourished families when, for example, it enthusiastically marketed a zero-caloric sludge as all there is to food.

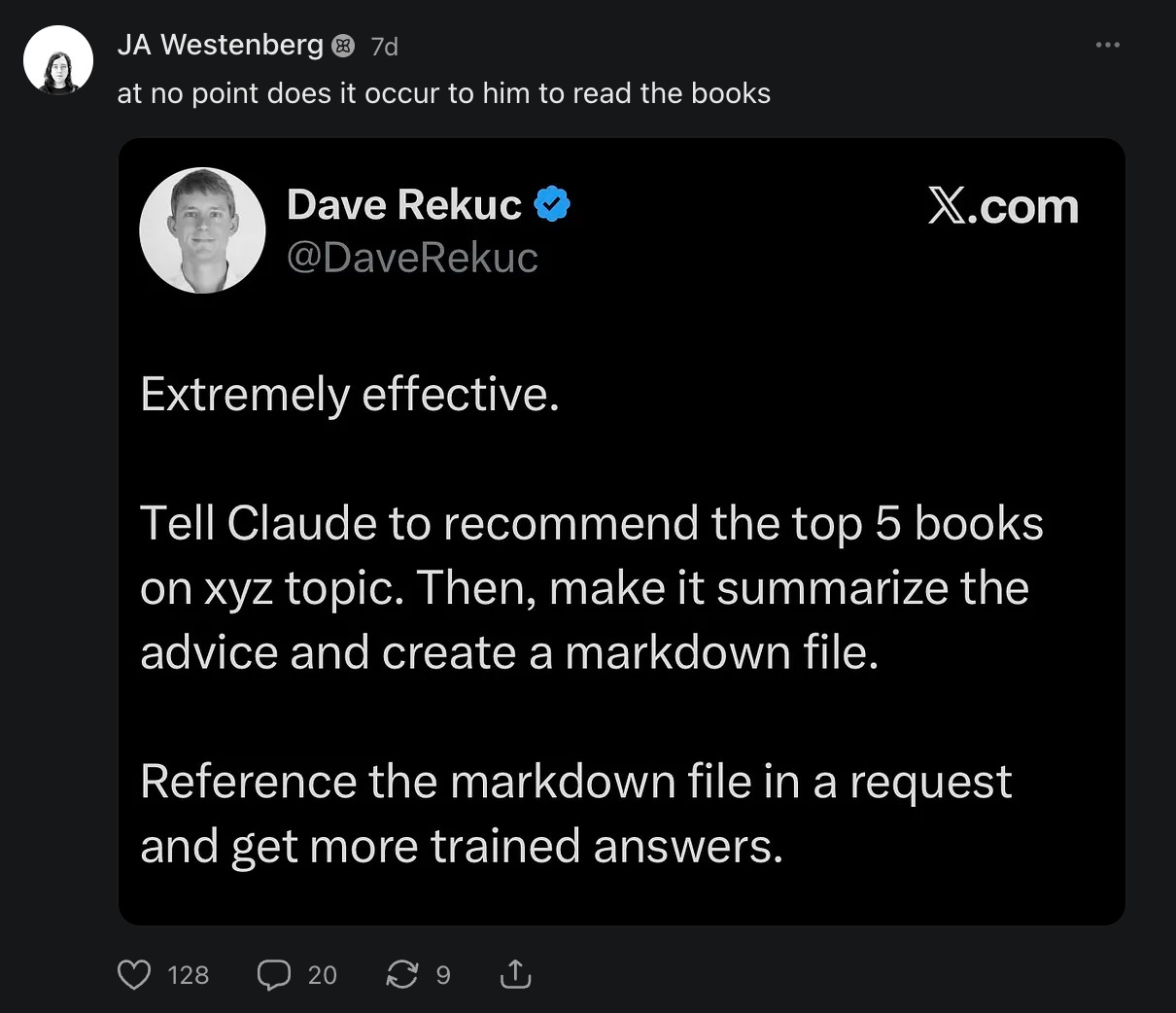

Now the focus of efficiencizing is on the intellectual and creative work, looking at it as a sum of the useful components - information, utility, efficiency, answers - that can be optimized for return-on-investment. There are strong opinions that there’s no tangible value in a whole-foods-type, human-made work, that reading an LLM-produced extract of a book is the same as reading the book; that LLM-written novels will be just as enjoyable as human-written ones; that there’s no place for visual artists anymore, since AI can do it all.

And I’m not convinced - we don’t know what we lose when we optimize away, but I’m paying attention to that gap.

The opposite argument - that there’s no place for AI in creativity and intellectual work - is equally hand-wavy, and obviously wrong. As much as I love my slow-grown organic tomatoes from a farm 2 hours away, I was also a steady fan of Huel during the height of gym days. I use LLMs in both my day job and creative work: to research, reframe, counterargue (and they’re great at that). I’ve also used them where original thought matters, like hypotheses or ideas or conclusions, with mixed results: useful, perfectly forgettable, and unfulfilling. Just like Huel.

Daniel Miessler has a good heuristic for this: everyone needs to decide for themselves what they consider “a job” and what’s “a gym”. At a job, the point is for the weight to be lifted and the work to be done. If tools make it easier and faster - all the better. But if you’re at a gym - the point is that you lift the weight yourself, repeatedly, to get better at it over time; push your limits, get stronger, more resilient.

Is “You are what you eat” now “you are how you think”? In pursuit of some goal, like getting the information required to do a job, it makes sense to go for efficiency. But I’ve noticed that in any other case, whether it’s my own or someone else’s original thinking - through books, essays, and art - I cringe away at the extracts (I’m looking at you, LinkedIn and Twitter threads). They feel food-like, like an intellectual equivalent of Soylent or Huel: fast, useful, tasteless and dead. And you feel that deadness, the gap where the connective tissue should be to something human.

I think similarly to the food scientists in the 1800s, we don’t have the name and definition yet for what exactly is missing.

Until then, we get to choose which culture we choose to participate in. Industrialization of food didn’t make everyone obese and unhealthy. But it did remove a somewhat healthy default of the pre-industrial-food reality: eating whole foods, moving a lot, dealing with the inconveniences of physically-demanding lifestyles and meals that don’t come in pre-packaged boxes. People bifurcated into those who took the new defaults and those who chose differently. The market also eventually pushed back: with fitness culture, the organic foods movement, farmers markets, and the revival of small agriculture.

Aside from the openly growing backlash against AI, I think we see more subtle symptoms of a broader cultural pushback, too: with Brick and dumb phones and Gen Z reviving fiction books, and even the emerging ideas around New Romanticism.

Here’s another thing to keep in mind for this parallel: 1800s nutritionists didn’t set out to undernourish a generation of people, but to solve a problem and build businesses. The model did end up advancing science (nutritionism did eventually give us baby formula and many healthy outcomes), it was commercially successful (the company behind the “zero caloric-sludge” did become a profitable conglomerate), and, unfortunately, it was also nutritionally catastrophic.

The technology conversation will stay similarly unresolved for a while. I’m a technologist, a node in the industrial system of Big Tech just as much as a creative human. I spend my days on ROI-positive applications of LLMs, and my evenings trying to figure out how my creative work fits in the same world, and, weirdly, I’m equally optimistic about both. This tension is pretty useful: on both fronts, I need to ask better questions; it makes it harder to be hand-wavy in either direction. Helps me to not slurp up everything without some scrutiny.